Part One: What is Artificial Intelligence?

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the single most overhyped area of technology I have ever encountered. The amount of misinformation and confusion around AI is staggering, so it’s the purpose of this set of tutorials to explain not just what AI is but also what it isn’t.

You can ask ten technologists what AI is, and you’ll probably get ten different answers, so with that in mind, let me at least start you with my answer.

It’s not Artificial Life

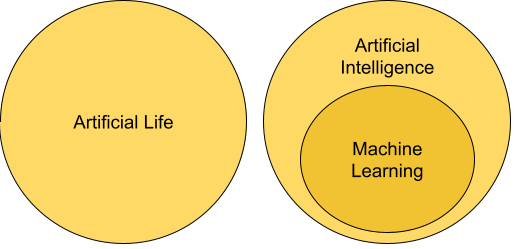

First of all, there’s Artificial Life sometimes referred to as Artificial General Intelligence (AGI).

AGI does not exist yet, and this has been the subject of speculative stories and prophecies for generations. These will often cast the artificial life in a negative light, with one of the oldest I have been able to find coming from the Biblical Book of Revelation, authored around 80AD, where future events concerning the end of the world involve several beasts. At one point, it describes:

"It ordered them to set up an image of the beast who was wounded by the sword but yet lived.

The second beast was given power to give breath to the *image* for the first beast,

so that the *image* could speak and cause all who refuse to worship the **image** to be killed"

Note that the word image here is a translation of the Greek word for statue, figure or representation. This word, in turn, derives from a word meaning something that is like another thing, an artificial copy of it.

Later literature doubles down on this fear of artificial life. While stories like ‘The Golem of Prague’ and ‘Frankenstein’ may appear primitive in terms of modern technology, the underlying tale dramatically resembles that of ‘Terminator,’ ‘Battlestar Galactica,’ and countless others in that artificial life is something that will destroy us, and needs to be feared.

And often, this type of artificial life is conflated with artificial intelligence, leading us to fear AI.

So let’s first put that stake in the ground in our definition of AI. It is not artificial life.

It’s not smart Computers

To understand what artificial intelligence is, let’s now turn to computing, and let’s try to understand what that’s all about. We often give computers credit for being smart, a meme brought about undoubtedly by science fiction, with the characters of shows like Star Trek able to talk to their computer and find out just about anything they need to know. Indeed, I remember, when at the ripe age of twelve years old, I got my first computer. I remember plugging it into the TV and starting to write programs in BASIC. A friend came round to see it, and when given a turn, the first thing he typed was “What is the capital of Brazil?”.

When the machine replied, “Syntax Error,” he was aghast. Computers were supposed to know everything. And while that misconception has gone away with more exposure of the general public to computing platforms, the underlying belief remains.

What computers are very good at is doing lots of monotonous, repetitive tasks very quickly. Programmers can create sets of commands that computers will act on, but in many ways, the actual intelligence and the problem-solving aspect comes from the programmer’s mind and not from the machine.

Since the dawn of computing, that’s been the job of programmers. Figure out how to solve a problem, break the steps of the solution down into simple-to-understand commands using a programming language, and then get the machine to do the job.

This process has been the bread-and-butter for the Computer Science industry for decades. Until the advent of Machine Learning.

It is just another algorithm

Now, while the term Machine Learning might make it sound like you are dealing with an artificial lifeform capable of learning in much the same way an actual lifeform would, that’s not the case. Machine Learning is still just a computer doing many calculations to make its program work a bit better, but automating the process instead of needing a programmer to figure it out.

Let’s consider an example here. We’ll start with a simple one for a human to program and use that as the basis for understanding how a machine can learn.

There are two main scales for measuring temperature globally, and these are Celsius and Fahrenheit. There’s a formula that connects the two of these, so you would figure out how to express that formula using a coding language.

So, for example, you might write:

def c-to-f(c):

f = (c*1.8) + 32

return f

You’d come up with this answer is because you probably looked up the formula for converting Celsius to Fahrenheit and then figured out the particular syntax to do that in a programming language such as Python.

Consider what would happen if you didn’t have the formula but still needed to figure out the relationship between the two values. Instead, you have a table of readings on both scales. What would you then do?

For example, you know that

- 10 degrees C is 50 degrees F

- 5 degrees C is 41 degrees F

- 0 degrees C is 32 degrees F

From the 0C = 32F relationship, you might surmise that the F value is 32+(something) times the C value. If that were the case, then you’d look at the 5C = 41F relationship and see that the 41 is 32+(1.8 times 5). You’d then verify this by calculating that the 10C=50F fit the same formula. You now know that the F value is 32 + 1.8 times the C value.

Note that there were two parameters in the above function. You calculated ‘f’ by multiplying ‘c’ by something (in this case, 1.8) and adding another something (32).

The key to Machine Learning: Pattern Matching

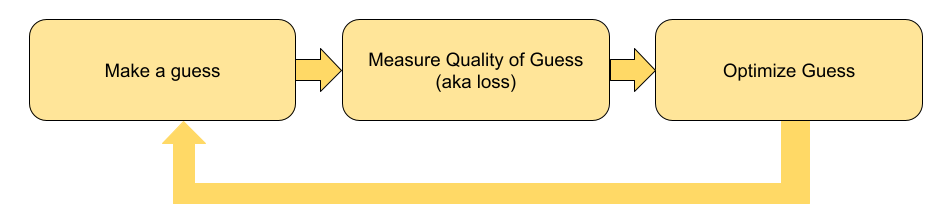

The process that we call ‘Machine Learning’ does a very similar thing, but a lot less smartly than you just did. It will guess the two parameters, and then, given the data, it will measure how good or how bad that guess is. That measurement is called a ‘loss.’ It will then strategize guessing to reduce this loss.

So, for example, it might guess that f = 10+(10c), initializing both parameters to 10. If it were to do that, then 0C would be 10F, which would be off by 22. Similarly, 5C would be 60F, and 10C would be 110F, both wildly incorrect. So the machine would strategize and use some fancy math to come up with another, better guess, maybe f=15+(5c). It would still be wrong, but less so. Getting closer and closer to the correct answer using brute force mathematics is commonly referred to as Machine Learning. So please, forget all those pictures of child-like robots sitting in a schoolroom. Those aren’t representative of Machine Learning at all!

For a trivial example like this, where it’s easy for a human to establish the rules, this may seem pointless. But what about circumstances where it’s tough for a human to see the rules that determine something? For example, what if you look at a picture like this. You can instantly tell that it’s a dog. But how do you have a computer recognize that? How can it tell the difference between a dog and a cat?

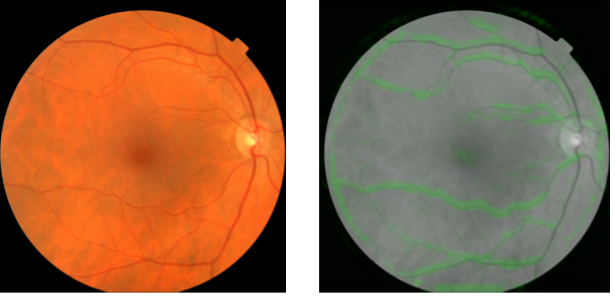

In a process similar to the above, you can have a computer look at lots of pictures of dogs and cats and use a similar brute-force method to find out what in the data distinguishes one from another. Surprisingly, recent research has shown that with the correct Machine Learning algorithm, computers are often better at humans at distinguishing visual objects. Not only that, researchers have been ab[le to use these algorithms to spot things in images that humans don’t see. There’s a famous story from Google Research. When exploring data from retina scans, a researcher noticed that gender and age data were available, so they wrote a Machine Learning algorithm to figure out a person’s age and birth-assigned gender from a retina scan. It proved to be more accurate than most humans at guessing these details!

This technique, Machine Learning, gives us a new way to program computers that behave more like intelligent creatures. So, instead of a picture just being numbers representing the dots that make it up, a computer can now figure out that it contains a cat, a dog, or a diseased retina. Or similarly, it can represent a sound as a type of bird, a regular heartbeat, or an alarm, instead of just a bunch of frequencies.

But, it is important to remember they are not alive, and they are not intelligent. And that is why the field is called Artificial intelligence.

In the next article in this series, I’ll go deeper into Machine Learning, look in more detail at some applications and how these applications can change the world for the better.